Toshusai Sharaku

Toshusai Sharaku (active 1794-95)

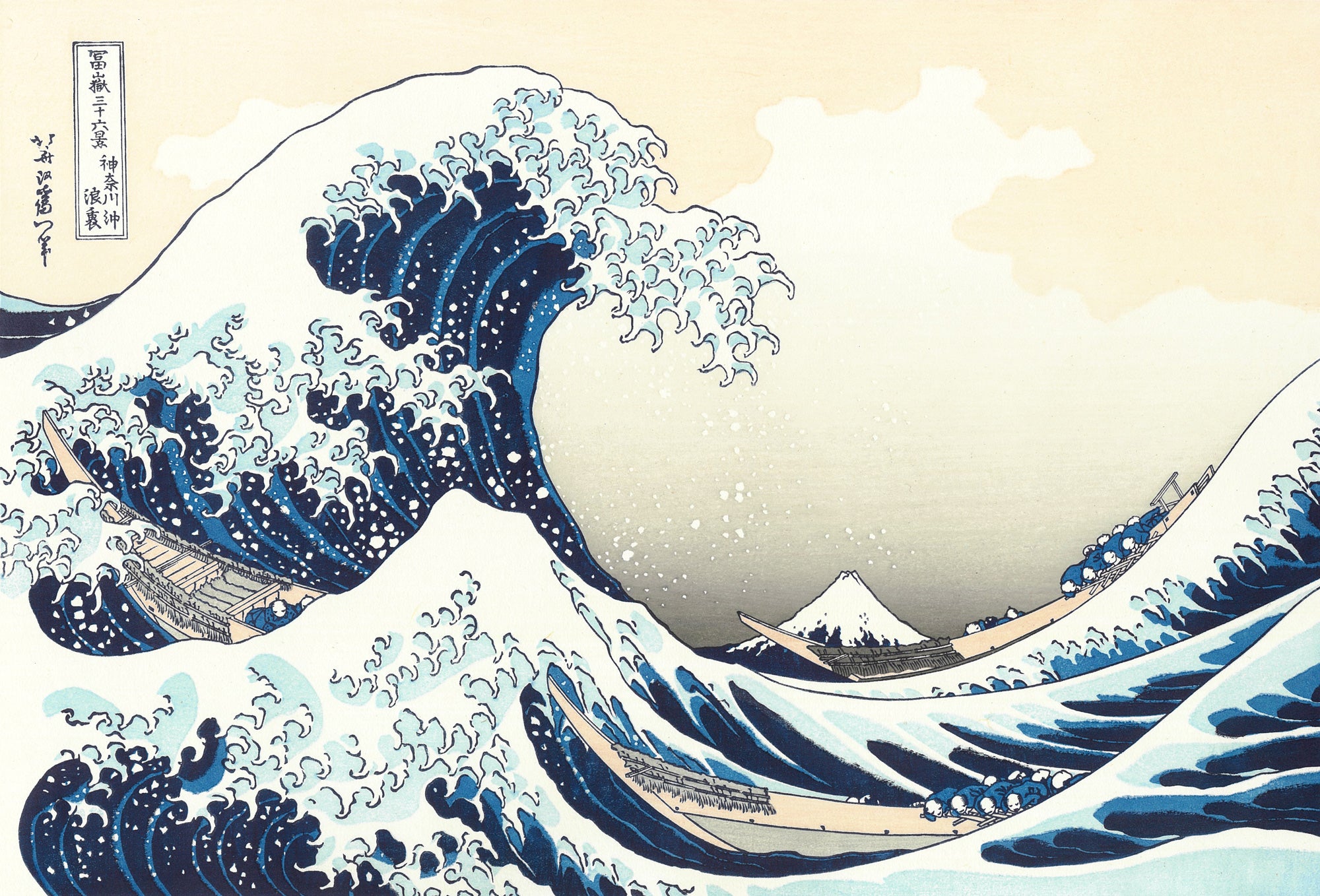

Sharaku was a remarkable ukiyo-e artist who appeared seemingly out of nowhere – like a comet – and disappeared just as suddenly. Working under the publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo, he produced more than 140 prints in the remarkably short span of just ten months, between May 1794 and January 1795. It is said that the brevity of his career may have been due to the unflinching realism of his portraits, which conveyed actors’ distinctive personalities without idealization––an approach that proved difficult for audiences of his day to accept.

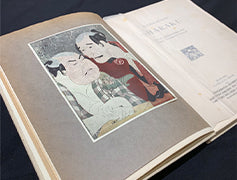

Nonetheless, his dynamic portrayals remain strikingly fresh even to our contemporary eyes. In the early 20th century, Sharaku’s work gained international recognition, thanks in large part to the German art historian Julius Kurth, whose book Sharaku introduced his prints to audiences abroad.

Many theories have been put forward regarding Sharaku’s true identity, but the most widely accepted theory today is that he was a Noh actor from Awa Province (present-day Tokushima Prefecture) named Saito Jurobei. Nonetheless, much about his career remains unknown, and Sharaku continues to be regarded as an ukiyo-e artist shrouded in mystery. The Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints has faithfully reproduced for future generations all of the surviving works of this enigmatic figure.

Sharaku and the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints:

The Founder’s Dedication and the Path to Full Reproduction of Sharaku’s Complete Works

Sharaku’s works, which have captivated viewers around the world, began entering overseas collections as early as the Meiji era (1868–1912). Some prints survive in only a single known impression, making it extremely difficult to grasp the full scope of his oeuvre. Motivated by a deep love for Sharaku’s art, Toyohisa Adachi, founder of the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints, launched a project to faithfully reproduce all of Sharaku’s known works scattered across the globe, in the hope of bringing them together and sharing their true appeal with a wider audience.

Toyohisa Adachi gathered reference materials from around the world and examined surviving works firsthand whenever possible. He devoted himself to faithfully reproducing the vibrant original colors as they would have appeared at the time of publication, and insisted on recreating each print at its original size. In an era when far less information was available and access to materials was limited, his dedication was truly extraordinary. In 1940, he completed 40 large oban-format prints, but the woodblocks and reference materials were later lost in World War II. Even so, Toyohisa never gave up, and after the war he resumed collecting materials with the goal of completing the reproduction project. Although the woodblocks for all of Sharaku’s works were finally assembled by 1978, Toyohisa passed away in 1983 before he could see the project through to completion. His vision was carried on by his successor, Isamu Adachi, and in 1984, more than thirty years after the project began, the full set of 142 prints was finally completed.

This reproduction project, which made the miraculous achievement of assembling all of Sharaku’s works possible, was acclaimed both in Japan and abroad for its scholarly value.

It also laid the foundation for the Adachi Edition of reproduced ukiyo-e, in which each print is meticulously hand-crafted using the same techniques as in the Edo period (1603-1868). To this day, it remains one of the most meaningful undertakings for us at the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints.

Founder Toyohisa Adachi (left)

The workshop at the time

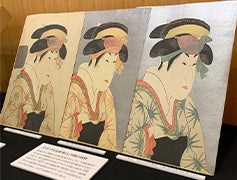

Full set of the complete works of Sharaku

First edition (1910) of Julius Kurth’s Sharaku, the progenitor of Sharaku scholarship

Materials for expert analysis of Edo-period (1603-1868) ukiyo-e prints

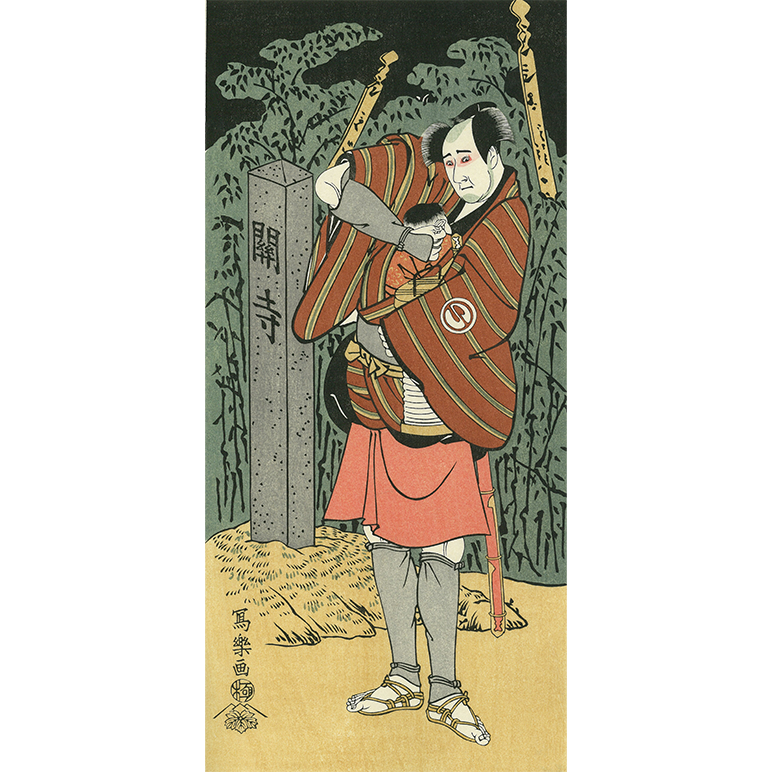

Sharaku’s Stunning Debut: First Period: Magnificent Portraits Capturing Actors’ Unique Character

28 Portraits in Oban Format with Mica

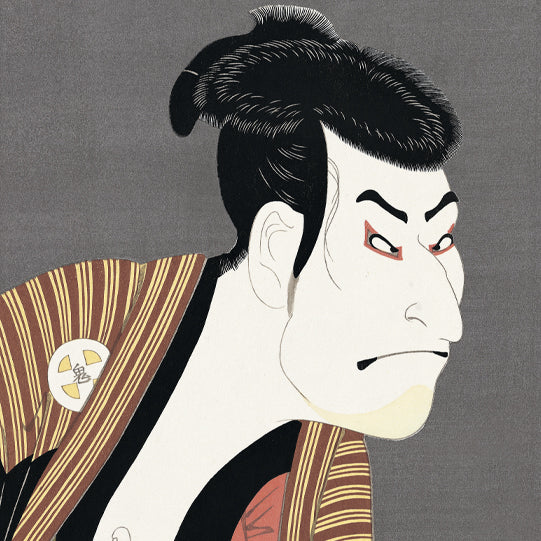

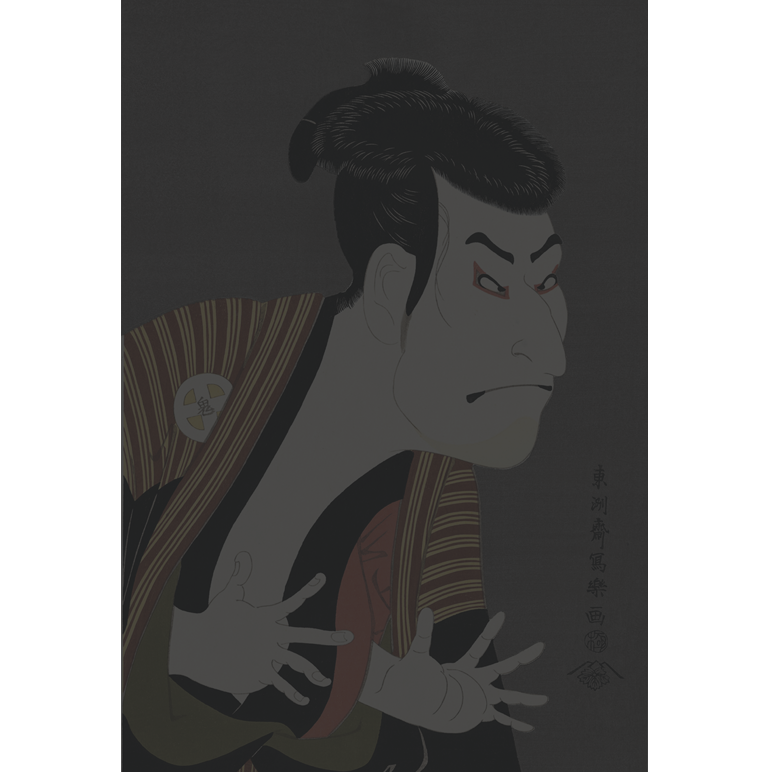

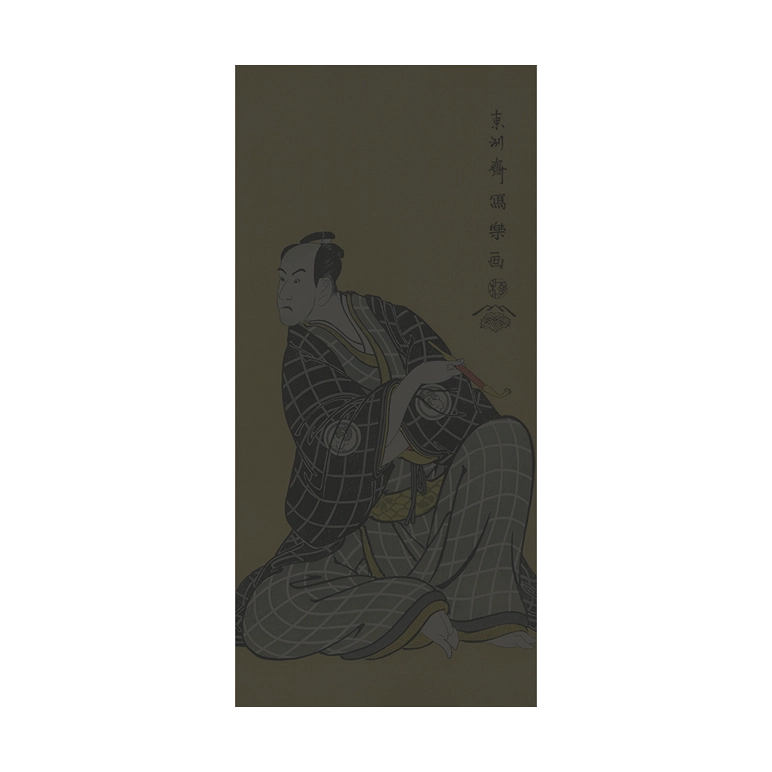

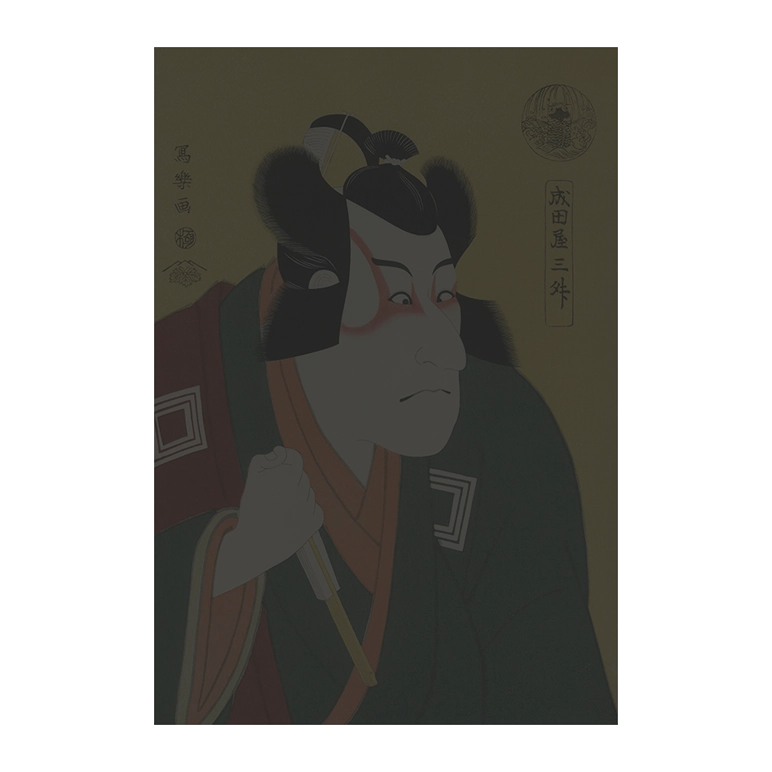

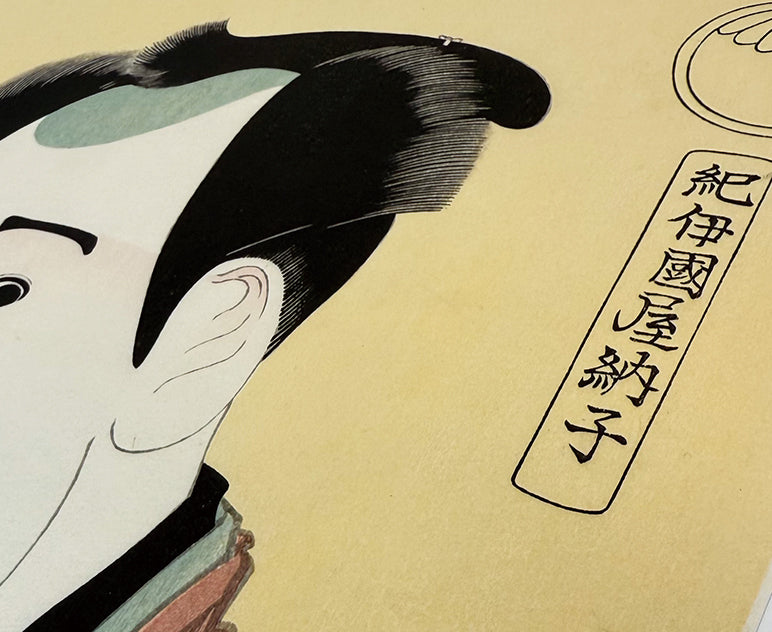

Sharaku’s career began in May 1794 with ukiyo-e prints depicting kabuki performances at Edo’s three major theaters. All 28 prints from this initial period were published in oban format, which was highly unusual for a newly emerging artist. These works also featured backgrounds finished with kurokira (black mica), a technique that enhanced the actors’ presence and lent the prints a sense of grandeur, vividly capturing the performers’ expressions as if illuminated by the dim light of the theater.

In these portraits, Sharaku rendered the unique features of each actor with striking realism. At the time,

most actor prints emphasized idealized beauty over accuracy, functioning more like glamorous publicity stills than faithful representations of stage scenes.

Sharaku’s unflinching portrayals, which defied these conventions, seem to have been difficult for the people of Edo to fully embrace.

Nonetheless, his actor prints scrupulously convey the plots of the plays, the characteristics of each role, and the actors’ gestures, expressions, postures, and even the subtle positioning of their hands and fingers. Through these details, one can sense not only the performers’ personalities but also their performance styles.

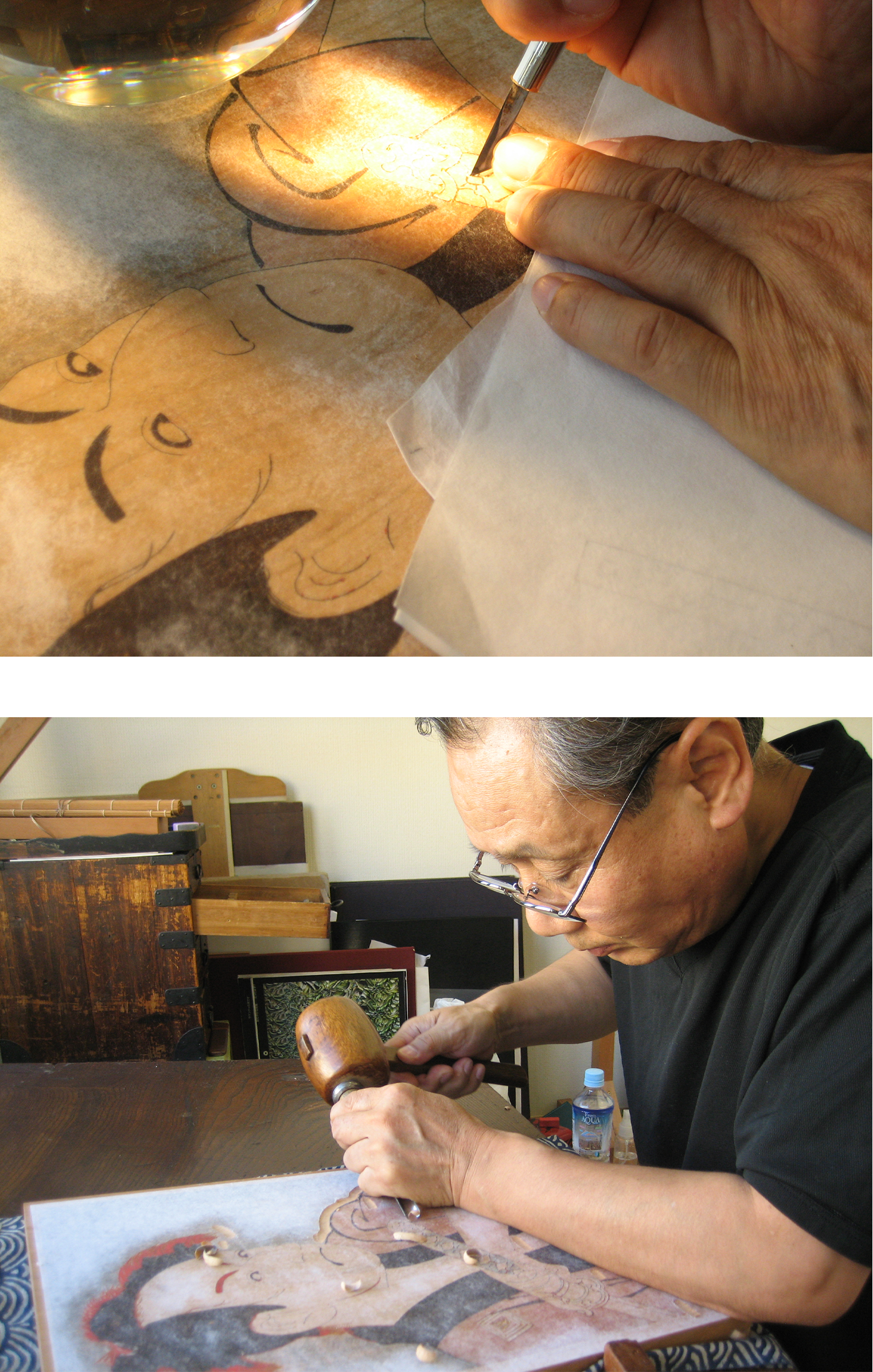

Niinomi, a master carver with 60 years of experience and a member of the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints, is widely regarded as a leading figure in the field. Known as the last pupil of the legendary master carver Okura Hanbei, he trained under Okura for eight years until his mentor’s passing, and joined the Adachi Institute in 1973. Over the years, Niinomi has worked not only on reproductions of ukiyo-e but also on numerous contemporary woodcut prints, including those by masters of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting).

Reflecting on Sharaku from a carver’s perspective, Niinomi says: “When carving to produce new editions of Sharaku’s works, I’m reminded anew of how not a single line is unnecessary. Sharaku’s prints were esigned to achieve maximum impact with minimal lines and colors, so each line is deliberate and the number is naturally limited. It’s especially difficult to carve the lines that form Sharaku’s inimitable facial expressions and the dynamic impact of the hands.

Also, since becoming a carver, I’ve come to question the commonly held belief that ‘Sharaku exaggerated individuality to the point that actors disliked his work.’”

“One work that made a stunning impression on me was The Actor Ichikawa Komazo III as Shiga Daishichi. I happened to see it at an exhibition when I was in university, and it inspired me to pursue a career as a carver. It’s still an unforgettable work for me. Since Shiga Daishichi is a villain, other ukiyo-e prints of Komazo in this role depict him with a menacing glare, like a stereotypical villain. By contrast, Sharaku’s portrayal has a surprising charm, and I feel it brings out the actor’s true appeal. It seems to capture not just the role he was playing, but also the humanity of the actor himself.”

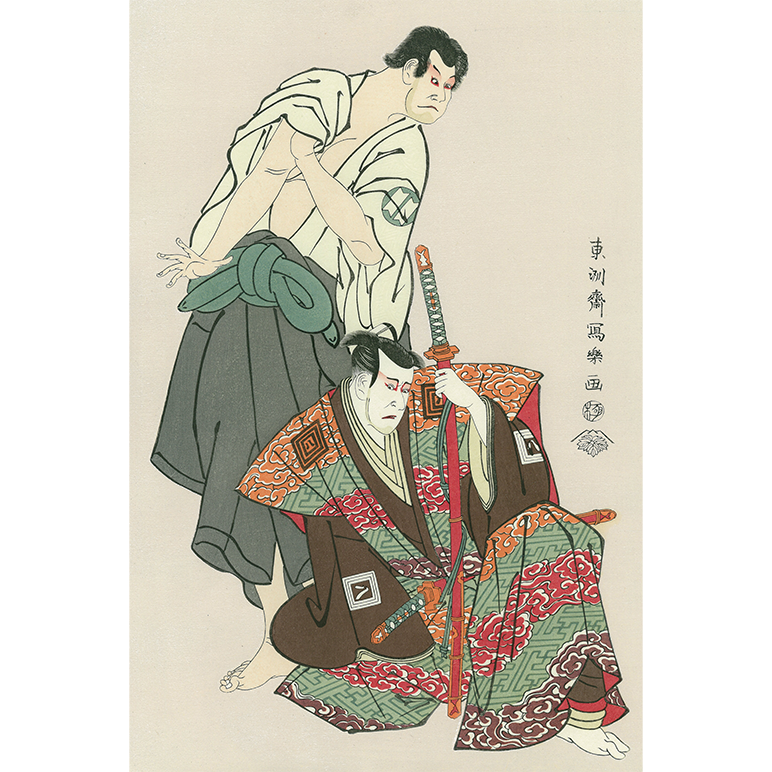

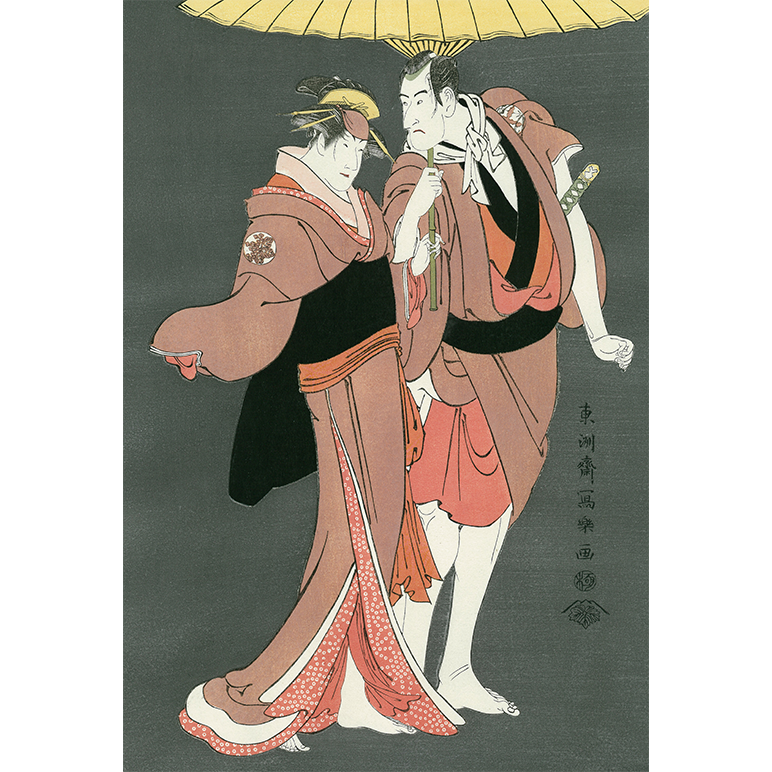

Stylistic Changes and Challenges: Second Period of Entirely New Actor Portraits

Pursuit of Visual Effects Through Nishiki-e Prints in Oban and Hosoban Formats

Sharaku’s second period comprises works based on kabuki performances staged in July and August 1794. In the print A Theater Manager, Reading the Program for the Next Round of Plays at Miyakoza, which portrays Miyakoza theater manager Shinozuka Uraemon announcing a play lineup, the paper he holds reveals faint text reading: “Announcement: From here on, we humbly present for your viewing a new, second series of portraits.” This inscription suggests that Sharaku was signaling a new direction in actor portraiture, distinct from his earlier approach.

Unlike the portraits of the first period, most of Sharaku’s second-period works depict full-body figures, capturing the actors’ movements and elegant poses through fluid curves. As in the first period, the backgrounds are left blank, but this time, solid yellow fills are frequently used. During this period, Sharaku produced prints not only in oban format but also in hosoban format. The oban prints often feature compositions that deftly balance two figures, while many of the hosoban prints were intended as part of sets that, when individual sheets are placed side by side, deliver the effect of famous scenes from the kabuki stage.

What Makes the Works Special? Key Terms for Understanding Sharaku

(1) Print Formats (Paper Sizes)

Sharaku produced works in a variety of sizes, but most strikingly, from the very beginning of his career – when his popularity was still uncertain – he boldly published 28 oban portraits of kabuki actors in half-length poses. Was the publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo so fully confident in Sharaku’s potential? Or was Sharaku in fact an already established artist working under an assumed name? The long-standing fascination with uncovering Sharaku’s true identity has been fueled in part by the remarkable support he received from the outset.

Note: Paper dimensions varied depending on the period and region.

Oban Format

This format is half the size of a type of washi paper called obosho, and was the most widely used format for nishiki-e (multicolored woodcut prints). While it was a common size, it was typically reserved for popular artists whose works were expected to sell well.

Hosoban Format

This format is one-third the size of kobosho, a type of washi paper slightly smaller than obosho. It was frequently used for actor portraits.

Aiban Format

This format is half the size of a sheet of kobosho, and was a convenient and affordable size often used for print series comprising many works.

(2) Backgrounds

It is striking enough that Sharaku debuted with 28 oban format portraits, but his prints also reveal remarkable attention to the treatment of background areas.

Black Mica (Kurokira)

In Sharaku’s first-period works, kurokira (black mica) was applied by placing a stencil over the figure and brushing on a glossy mixture of mineral mica, ink, and animal glue. This striking effect made the figures appear more vivid and dramatically illuminated.

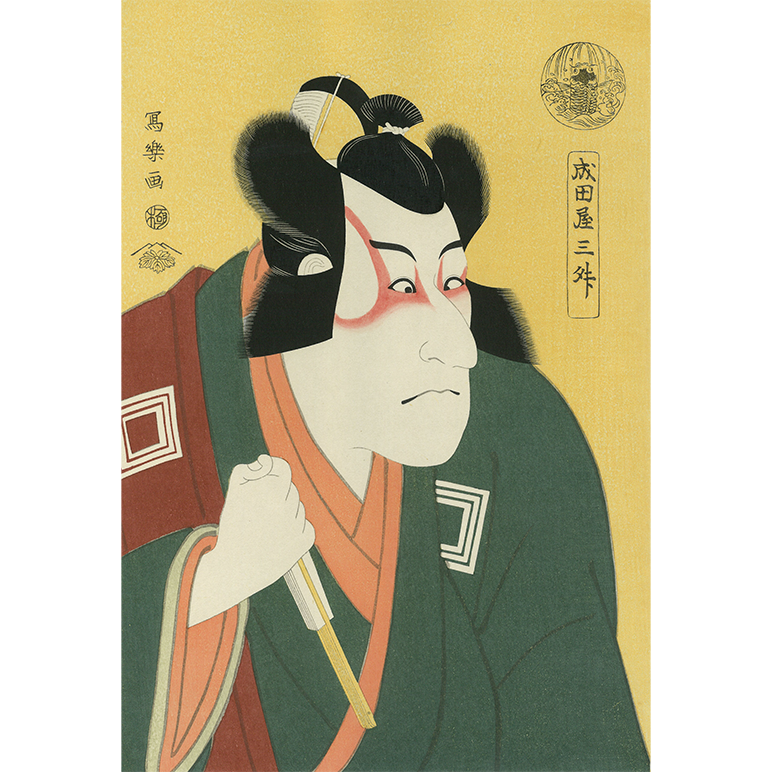

Yellow Fill (Kitsubushi)

From the second period onward, many of Sharaku’s prints feature kitsubushi, backgrounds filled with a uniform yellow color. Though seemingly simple, achieving a smooth, even application over a large area required exceptional skill on the part of the printer.

Third Period: Vivid Depictions of Special Kabuki Performances

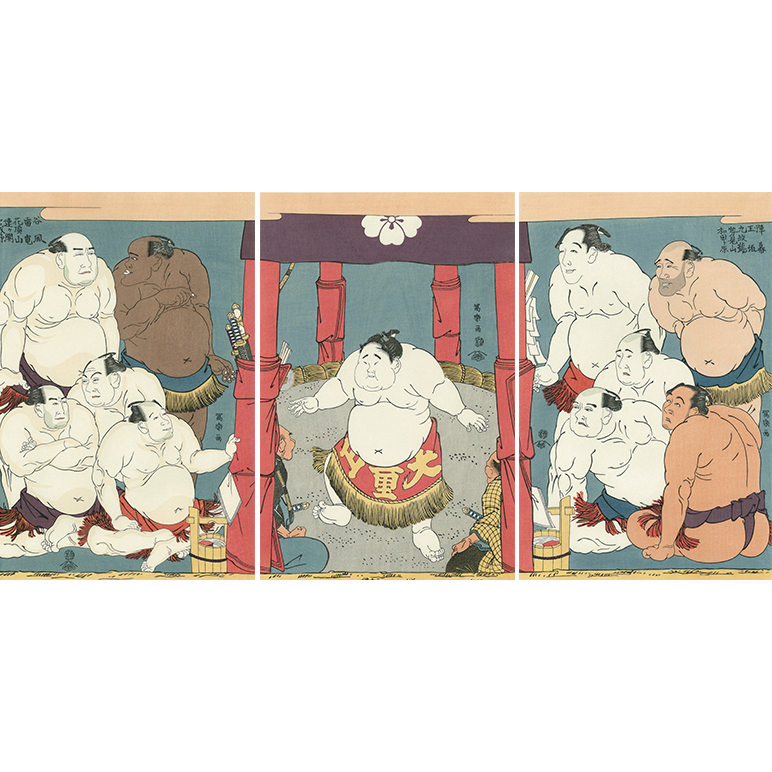

Actor Prints in Aiban and Hosoban Formats, Sumo Prints, and Memorial Prints

The works from Sharaku’s third period are based on kabuki performances held in November 1794. At

the time, November held great significance on the Edo kabuki calendar, with special performances staged to introduce new actors.

During this period, Sharaku produced aiban-format prints featuring half-length portraits with kitsubushi (yellow fill) backgrounds, while continuing to produce full-body hosoban-format prints as in the second period. A notable shift from the previous phase is the inclusion of backgrounds in the hosoban prints. This period is marked by a more decorative style, with a vibrant and ornate visual character.

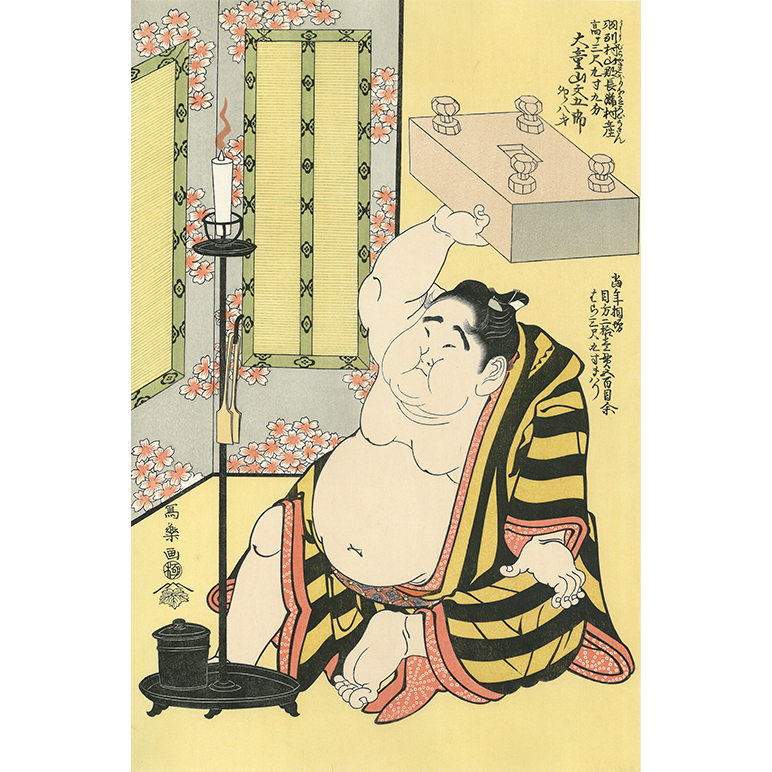

Sharaku also expanded his subjects beyond actor portraits. He produced sumo prints depicting Daidozan,

a young wrestler who gained popularity in Edo after performing the ring-entering ceremony in kanjin-zumo (promotional sumo) at the age of seven. He also created memorial prints honoring beloved actors who had passed away.

Fourth Period: Increasing Depictions of the Stage

Hosoban Format Actor Prints and Sumo Prints

The works from Sharaku’s fourth and final period consist of hosoban-format prints based on comedic New Year’s plays staged in January 1795. In this phase, he further refined the background details introduced in his third-period hosoban works, rendering them with even greater intricacy. These descriptive backgrounds emphasize the fact that the scenes are on stage, while by contrast, lines depicting the actors and their costumes became noticeably simpler.

Sharaku also continued to produce sumo prints during this period.

After completing these works, this extraordinary ukiyo-e artist vanished from the historical record.

Featured Products

2 colors available