Kitagawa Utamaro

Kitagawa Utamaro (1753?-1806)

Utamaro stayed with the great publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo and made illustrations for kibyoshi and sharebon books. Influenced by Kitao Shigemasa and Torii Kiyonaga, he began to draw full-length portraits in the Tenmei era (1781-89).

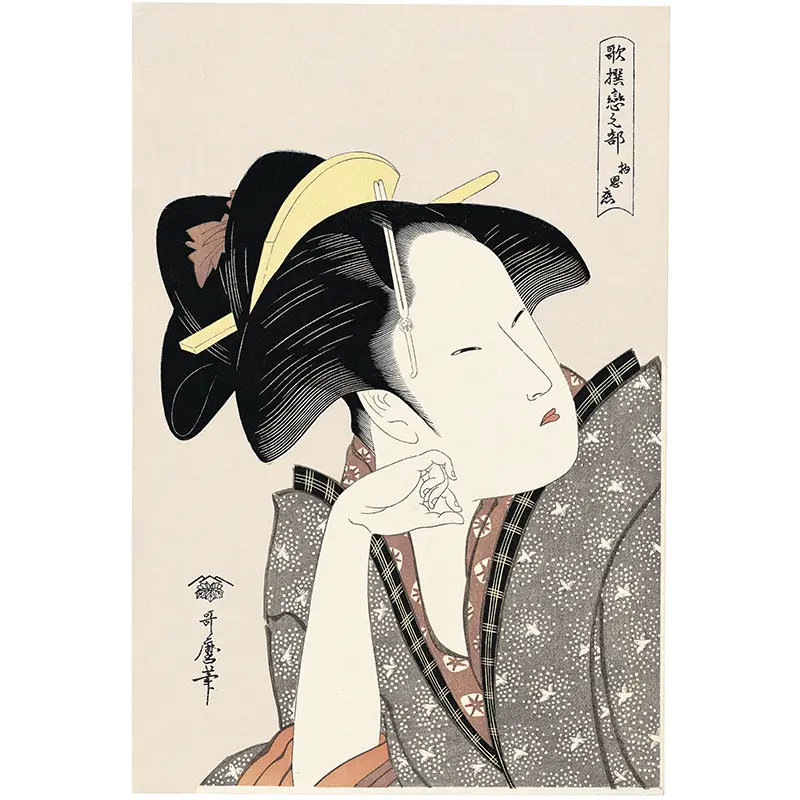

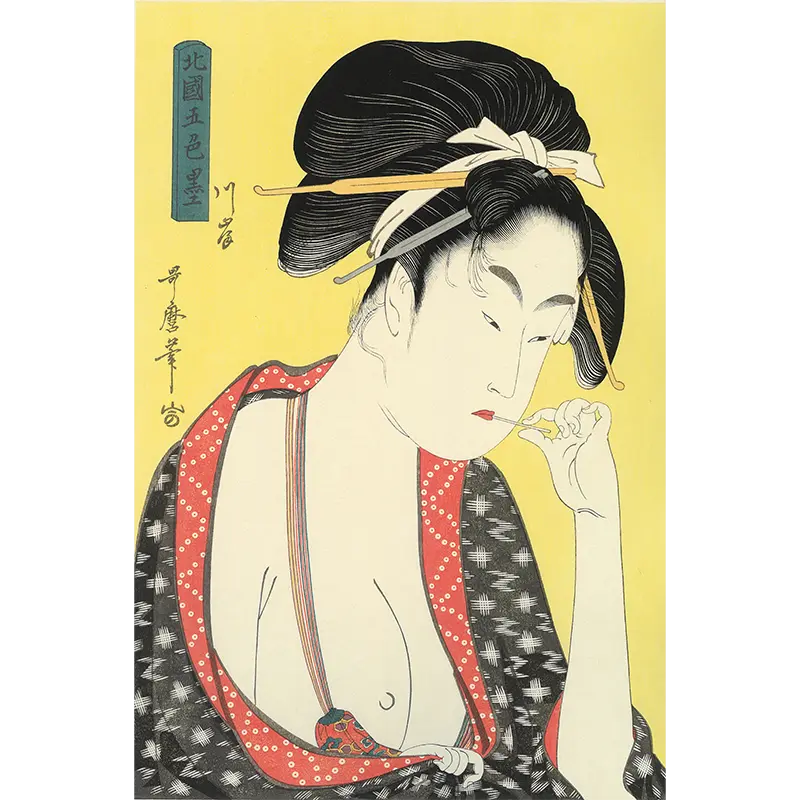

Later on, during 1790-91, Utamaro established his own style depicting three-quarter portraits of the beauties.His work became very popular because of his vivid new way of reproducing beauties, and his reputation as a master artist was established.

Enjoy with themes

Kitagawa Utamaro, the master of bijinga, and Tsutaya Juzaburo

A large number of the works of Utamaro were produced by Tsutaya Juzaburo (aka "Tsutaju") including many of Utamaro's most important works.

So what kind of man was the publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo?

According to records, Tsutaya Juzaburo was born in Yoshiwara in 1750, about three years before Utamaro. From around 1774, he was involved in the publishing and sales of a guidebook to the famous red-light district entitled "A guide to the Yoshiwara licensed quarter" and he went on to establish a new business style and become a prominent publisher in Edo. Tsutaju did not limit himself to publishing and sales. He made bold changes to "A guide to the Yoshiwara licensed quarter" to make the publication more entertaining for readers and asked popular authors to write prefaces. He went beyond the bounds of publishing and took on various projects, much like a modern-day producer. Tsutaju provided a breath of fresh air to the publishing world and produced one hit after another from his headquarters in Yoshiwara. In 1783, he opened a new store in Nihonbashi and emerged as a power to be reckoned with in the publishing world.

It was Tsutaju who set his eyes on Kitagawa Utamaro (1753? -1806) as a new generation artist.

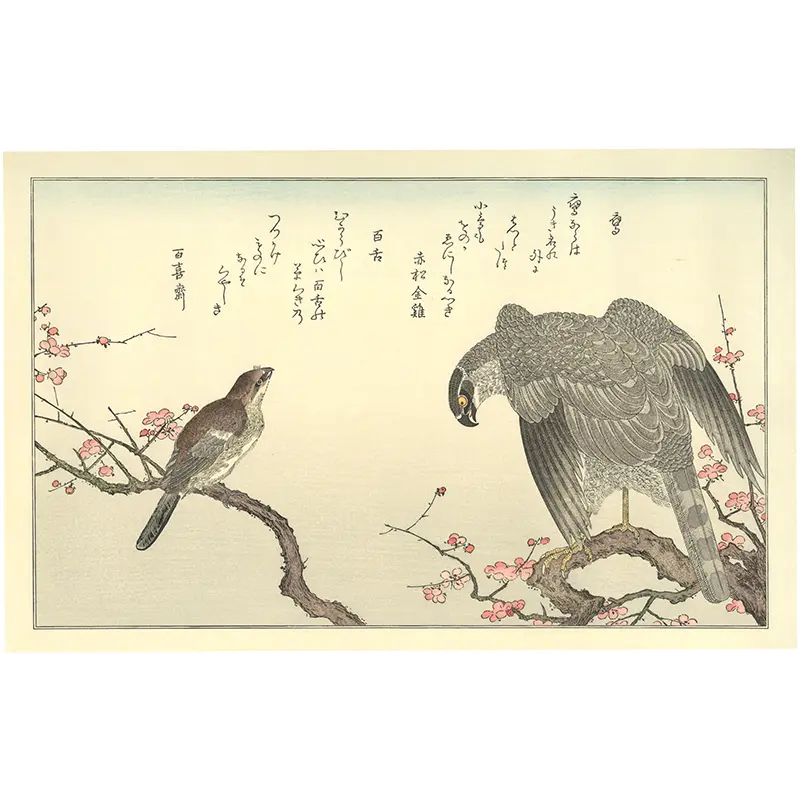

The name Utamaro became widely known when he drew illustrations for kyoka-bon (books of humorous poems) that Tsutaya published from around 1788. Kyoka-bon were popular at the time, and Tsutaya published collections of poems with pictures of wildlife entitled "Ehon mushi erami (Picture Book of Selected Insects)," "Shiohi no tsuto (Gifts from the Ebb Tide)" and "Momochi dori (Myriad Birds)." Utamaro's illustrations were realistic representations of the subjects, completely different from the portraits of beautiful women (bijinga) Utamaro is known for today, but they demonstrated Utamaro's outstanding skills as an artist.

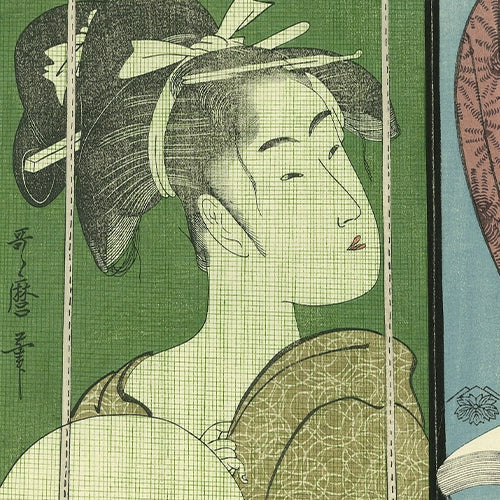

Originator of "Okubi-e," Portraits Focusing on the Upper Half of a Woman's Body

After the success of the illustrations for kyoka-bon published by Tsutaya, Utamaro teamed up with Tsutaju to release numerous bijinga. In particular, the type of ukiyo-e called okubi-e became a sensation in Edo. Okubi-e focused on the upper half of the subject's body. Utamaro and Tsutaju took this format, which was previously used in yakusha-e (pictures of kabuki actors) and applied it to bijinga. Focusing on the upper body made the woman's face more prominent. Utamaro took advantage of the format to capture the inner beauty and personalities of each woman in his portraits. Prior to this time, artists' ideals of feminine beauty were reflected in the portraits. In contrast, Utamaro's bijinga were portraits of real women.

Moreover, as the women's facial features were depicted in more detail, great precision was required to carve the facial features and the edge of the hair on the forehead. Therefore, Utamaro's works contributed to the advancement of woodcut print production techniques.

Numerous Hits Produced in the Kansei Reforms Era

However, these were the days of the Kansei era (1789-1801), when a series of conservative measures were promoted. People were urged to live frugally, public morals were strictly enforced, and restrictions were placed on entertainment, including the publishing industry. Even in such times, Tsutaju and Utamaro went against the shogunate's policies and continued to explore ways to make beautiful portraits of women, opening up new possibilities for bijinga.

One new invention was bijinga with shining backdrops created by applying kira (mica) to the surface. In response to government orders to make ukiyo-e more plain, Tsutaju and Utamaro came up with the idea of not drawing anything in the background and applying mica powder to create a shiny finish instead.

Applying the mica powder

The technique called kirabiki made Utamaro's bijinga a great hit among the people of Edo.In addition to kira backgrounds, Utamaro invented a variety of new methods through trial and error and in response to the government restrictions. He looked at women through translucent materials to bring out their beauty, and used karazuri embossing to convey the softness of a woman's complexion.

He employed such methods in an attempt to capture the true essence of various women who exist in the real world. The 12-part series "The Twelve Hours in the Yoshiwara" showed a day in the life of courtesans in the red-light district by taking a "snapshot" once every two hours. It was highly regarded as a work that not only captures the enchanting atmosphere of the district but also gives a glimpse of the true face of the women working there. Utamaro was able to create this series thanks to Tsutaju, who was very familiar with Yoshiwara.

The Last Days of Tsutaya and Utamaro

In 1791, however, the shogunate convicted Tsutaya for publishing multiple illegal materials and confiscated half of his estate. After this setback, Tsutaya promoted the enigmatic artist Toshusai Sharaku and made other attempts to revive his business but succumbed to a disease in 1797.

After the passing of Tsutaju, Utamaro continued to produce numerous bijinga as an artist, but in 1804, he was sentenced to 50 days of home arrest in handcuffs over paintings in which he depicted forbidden subjects. His health deteriorated, and he died in despair two years later.

Publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo and artist Kitagawa Utamaro were born around the same time and their lives came to a similar end. However, the world of ukiyo-e and bijinga greatly evolved thanks to the outstanding work of these two men. As the relationship between Tsutaju and Utamaro demonstrates, publishers in the Edo Period played an important role, much like today's producers. The planned projects, selected artists and worked as a coordinator for artists, carvers and printers, and were deeply involved in all stages of the publishing process. Without Tsutaya Juzaburo, the world would not have known Kitagawa Utamaro, the master of bijinga. Tsutaju and Utamaro were united as adventurers and revolutionaries in the world of ukiyo-e.